Unfinished Inventory of Animals Eaten in Cities During Times of War and Siege

This inventory is an under-construction historical overview of survival techniques and sources of food that have been improvised, hunted and innovated in the urban environment under the extreme conditions of war.

Haarlem, 1573

In 1573, when Haarlem was kept under seige by the Spanish anything with legs, feathers or gills was wolfed down in hunger. Dog liver and kittens were deemed haute cuisine demanding exorbitant prices on the black market. During the seige, the citizens of Haarlem consumed dogs, cats, horses, mice, rats and pigeons.

…through the month of June, the sufferings of the inhabitants increased hourly. Ordinary food had long since vanished. The population now subsisted on linseed and rape-seed; as these supplies were exhausted they devoured cats, dogs, rats, and mice, and when at last these unclean animals had been all consumed, they boiled the hides of horses and oxen; they ate shoe-leather; they plucked the nettles and grass from the graveyards, and the weeds which grew between the stones of the pavement, that with such food they might still support life a little longer, till the promised succor should arrive. — John Lothrop Motley, The Rise of the Dutch Republic, 1855.

Paris, 1590

A similar destiny was expected for horses, dogs, donkeys, cats and rats in Paris under the siege of Henry IV. Astonishing is a ‘recipe’ for bread including bran and cats [!]. Ca va sans dire, aristocracy liked aristocratic dogs better.

Most of the people began to eat bread made of cats and of bran, and even so it was rationed… Horse meat was also so expensive that the little people could not buy it; they had to hunt dogs and eat them, and raw herbs without bread, which was an ugly and pitiful thing to behold. — Pierre de L’Estoile quoted in Julien Coudy (ed.), The Huguenot Wars, Philadelphia: Chilton, 1969.

But Paris, with its walls and gates and iron chains, could not be supposed to be sleeping tranquilly when those who stood on Notre Dame looked out as hopelessly and as helplessly for succour as shipwrecked mariners for friendly sail. The prices of provisions rose rapidly as the army of Henry of Navarre arrived and settled down before the walls of Paris. The famine fell on the poorest first; only the rich could buy bread and meat, and the rations served out were scanty. As the summer advanced the sufferings of the citizens became more terrible. Horses, dogs, asses, cats and even rats were ravenously eaten. The Duchess de Montpensier refused gold and jewellery to the amount of two thousand crowns for a favourite dog, saying she would reserve it for herself when her stores were exhausted. No less than thirteen thousand persons are estimated to have died of hunger during the blockade. —John Tillotson, Stories of the wars 1574-1658, Oxford: 1865.

Paris, 1870

Parisiennes ate dogs during the siege of Paris in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71). Poodle was supposed to be the best meat of dog breeds. One famous 1871 illustration of butcher’s shop at Mont Martre in Paris shows the sale cat, rat and dog meat.

It is estimated that during the siege of Paris in 1870 over 5000 cats were slaughtered and eaten. A young cat, it was found; tasted like a squirrel but was tenderer and sweeter. — Current Opinion, Current Literature Pub. Co, 1890, p. 379.

Over the duration of the siege, the Academy of Sciences advised on converting all animal remains into meat replacement gelatine and urged the advantages of hippophagia and turning horse fat into ‘Parisian butter’ and to even rehydrate the albumen in printed textiles to substitute the lack of eggs and converting candle fat into fat for frying.

Paris, 1871

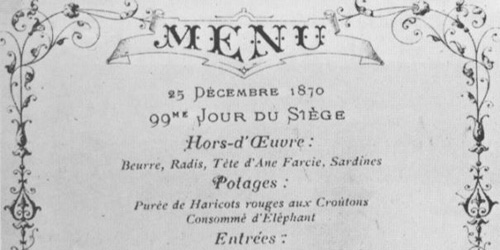

Following France’s defeat was the Paris Commune, the French revolution of 1871. As well as dogs, (rich) Parisiennes resorted to eating the elephants of the Paris zoo at the Jardin des Plantes: Castor and Pollux, as well as cats, rats and seagulls. Even expensive resturants made gastronomical innovations using elephant meat and seagulls for a gull pie. Here is a picture of a Christmas Day menu (at the 99th day of siege) featuring fine wines and dishes with ‘exotic’ animal meat such as elephant, wolf, and camel.

The vin ordinaire is giving out. It has already risen nearly 60% in price. This is a very serious thing for the poor, who not only drink it, but warm it and make with bread a soup out of it. Yesterday, I had a slice of Pollux for dinner. Pollux and his brother Castor are two elephants which have been killed. It was tough, coarse and oily, and I do not recommend English families to eat elephant as long as they can get beef or mutton. Many of the restaurants are closed owing to want of fuel. They are recommended to use lamps; but although French cooks can do wonders with very poor materials, when they are called upon to cook an elephant with a spirit lamp the thing is almost beyond their ingenuity. Castor and Pollux’s trunks sold for 45fr. a lb.; the other parts of the interesting twins fetched about 10fr. a lb. [...] The Zoological Gardens have been shut. Why? Because the elephants, the tigers and other rare animals have been sold in order to enable wretches who laugh at the public misery to gorge themselves. — Henry Labouchère, Diary of the Besieged Resident in Paris, Project Gutenberg, 2006.

When vegetables, butter, milk, cheese and the regularly consumed meats began to run out, the Parisians turned first to horse meat. Horse meat had been introduced by the butchers of Paris four years earlier as a cheap alternative source of meat for the poor, but under siege conditions it quickly became a luxury item. Though there were large numbers of horses in Paris (estimates suggested between 65,000 and 70,000 were butchered and eaten during the siege) the supplies were ultimately limited. Champion racehorses were not spared (even two horses presented to Napoleon III by Alexander II of Russia were slaughtered) but the meat soon became scarce. Cats, dogs and rats were the next selection for the menu. There was no control over rationing until late in siege, so while the poor struggled, the wealthy Parisians ate comparatively well; the Jockey Club offered a fine selection of gourmet dishes of the unusual meats including Salmis de rats à la Robert. There were considerably fewer cats and dogs in the city than there had been horses, and the unpalatable rats were difficult to prepare, so, by the end of 1870, the butchers turned their attentions to the animals of the zoos. The large herbivores, such as the antelope, camels, yaks and zebra were first to be killed. Some animals survived: the monkeys were thought to be too akin to humans to be killed, the lions and tigers were too dangerous, and the hippopotamus of the Jardin des Plantes also escaped because the price of 80,000 francs demanded for it was beyond the reach of any of the butchers. Menus began to offer exotic dishes such as Cuissot de Loup, Sauce Chevreuil (Haunch of Wolf with a Deer Sauce), Terrine d’Antilope aux truffes (Terrine of Antelope withtruffles), Civet de Kangourou (Kangaroo Stew) and Chameau rôti à l’anglaise (Camel roasted à l’anglaise). — Wikipedia, “Castor and Pollux elephants“

Amsterdam, 1944-1945

At the end of World War II, pigeons, seagulls, swans, rabbits, cats were eaten during the severe conditions of the Hongerwinter (’hunger winter’) when Amsterdammers turned to hunting the city parks and nature beyond the city. City biologist Remco Daalder has written how some people caught seagulls by luring them with breadcrumbs. Tulip bulbs and sugarbeets were commonly consumed. From 29 April to 8 May 1945, Operation Manna took place. Lancaster bombers of the Royal Air Force dropped food into parts of the occupied Netherlands, with the acquiescence of the occupying German forces, to feed people who were in danger of starvation. Earlier, there had been a distribution of white bread made from Swedish flour that was shipped in and baked locally. A popular myth holds that this bread was dropped from airplanes, but that is a mix-up between the two events. Also, the food was not dropped with parachutes, as is often said.

See also:

– Remco Daalder, Stadse Beesten, Amsterdam: Bas Lubberhuizen, 2005.

– David Barnouw, De hongerwinter, Hilversum: Verloren, 1999. [on Google Books]

– Bibliography of Dutch Famine of 1944 also known as the Hunger Winter– Bertrand Taithe, Defeated Flesh: Welfare, Warfare and the Making of Modern France, 1999.

Sarajevo, 1992 -1996

War famine is not a distant scenario. Much more recently, in Sarajevo under the nearly 4 year siege of the Serbian army, inhabitants turned to any potential food substance found in the city parks. Snails, Fir-tree juice, Birch sap, Nettle pie. Pigeons were one of the desperate source of food as many newspapers reported.

For Ivana Benic and her family, surviving in the beleaguered Bosnia-Herzegovina capital of Sarajevo meant having to eat pigeons. “We trapped them on the window sill using an improvised net. But, since the fighting has become worse, the birds have fled.” — Jonathan S. Landay,”Help Seems Remote in Besieged Sarajevo“, The Christian Science Monitor, 12 June 1992.

Animals not eaten in times of war

Animals have been employed for the most diverse uses in time of war. In this picture a dog with a gas mask during World War II (Francis Whiting Halsey, The Literary Digest History of the World War, volume V, 1920, p. 333). See also the Wikipedia entry ‘Military animal‘ and this photo gallery about animals at war.